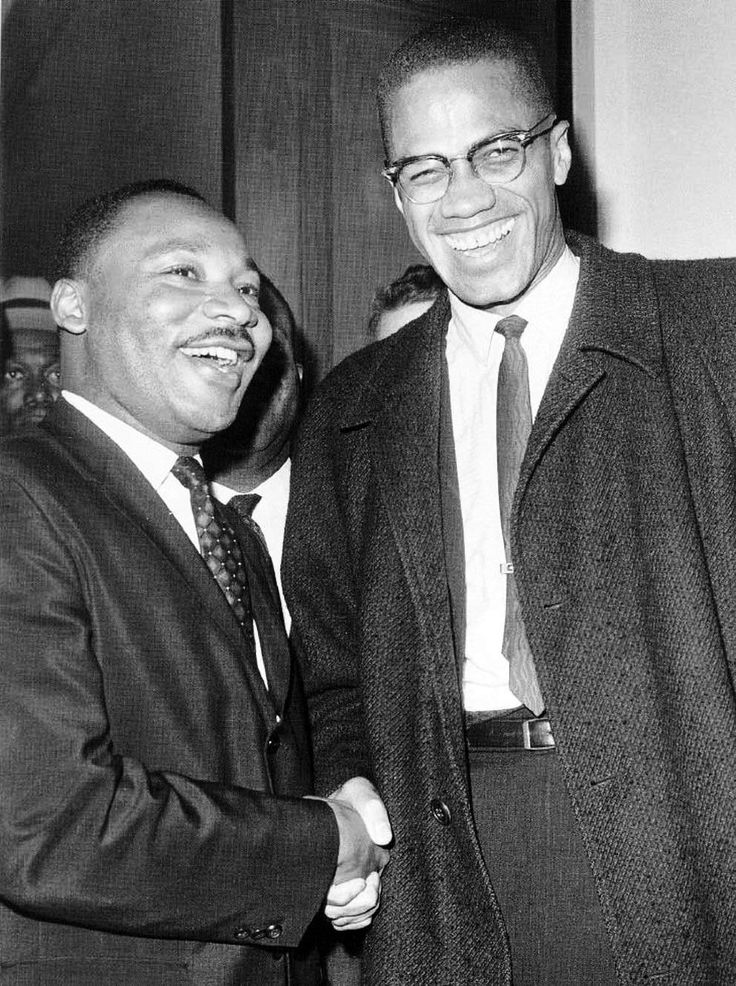

MARTIN and MALCOLM: “Two Legacies, One Movement”

Elizabeth A. Singleton

Introduction

Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, both historical icons dominating the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s, made profound psychological, political, economic and spiritual impacts on the development of the African American community and upon the social landscape of this nation. Although their lives were cut short, they ignited international attention that sparked a previously unknown upsurge of freedom fighters throughout the Third World. As activists, both men realized that the African community residing in America had to pave its way. It’s humanity, its dignity and its constitutional rights were not guaranteed nor upheld by the governing body of this land.

And so amid suppressed confusion, anguish and hostility within the Black community towards a society in which it was consistently treated as a second-class citizen, there arose two distinct leaders, each walking separate paths with the one ultimate goal of “freedom.” Although they had different appeals, both came to the root of the matter with one agenda — liberation for all people.

Martin was the cultured, educated, middle-class minister. Malcolm was the grew-up-against-all-odds hustler and ex-convict turned minister. Martin was nurtured in the traditional values and “Jim Crow” caste system of the South, and Malcolm was nurtured in the urban values and institutional inequities of the North. Neither was isolated from the pain and violence of racism. Both grew up in separate and unequal societies. Both rose to the beckoning cry of their people, who had come out of four centuries of slavery. Each had to confront the highest law of the land, the Supreme Court, with its historical legacy of prejudice, to forcefully proclaim to this government to “let our people go.”

Martin’s approach was to jolt the system through direct protest, non-violent demonstrations, and peaceful yet meaningful marches with economic boycotts to command attention from the establishment. Malcolm’s approach was to more aggressively seek separation, for Black people to become more economically viable, socially strengthened, culturally exposed and politically astute. To build a nation within a nation.

Both men were psychologically complex leaders who instinctively realized the responsibility they were asked to undertake. Martin awakened from the pulpit and Malcolm awakened from prison.

Malcolm and Martin were committed to the continual development of their minds. Martin began his development through a formal education, acquiring a Ph.D. in theology by the time he was 26. He continued his education during his movement days, attracting talented and committed people to serve on the SLC staff. He also organized a research committee and New York advising group of professionals and intellectuals. He frequently held retreats to debate the issues of non-violence, civil disobedience, Black Power and Vietnam. It was he who said, “We have a moral responsibility to be intelligent.”

Malcolm initiated his intellectual development with a program of study in prison, copying words from the entire text of the dictionary. After this painstaking, tedious work, he was then able to read books with understanding. He regretted his lack of an academic education because he realized that it hindered his ability to defend the humanity of Black people. “I wish I had been…a lawyer”, because, as he once said, “I’ve always loved verbal battle and challenge.” “Of all the studies, history is best qualified to reward our research,” he often said. Martin was an avid reader who devoured books, sometimes in a single evening. Like Martin, he used his knowledge to empower and challenge African-Americans to study their past, so they could know what to do in the present to direct the future for themselves, their children and generations to come.

Martin became a catalyst for economic empowerment as well as a force in bringing the Black community to a realization of its consumer strength and impact on the financial confines of corporate wealth. Corporate America could not conduct business as usual without the Black community’s dollars, and now there was a way to prove it:

Rosa Parks, after paying her fare on a bus one day, said she would not get up and sit at the back of the bus for a White rider. This sparked the Montgomery bus boycott, which was a clear and open message to the world that the Black community would no longer tolerate unequal treatment for equal pay. In the wake of the Montgomery bus boycott, there emerged the sit-ins, freedom rides, March on Washington, Selma March and many other marches and demonstrations throughout the South – all of which involved the masses of Blacks who prefaced their rebellion within the spiritual context of Martin’s non-violent direct action.

Protesters faced the head-on violence of White policemen and other atrocities. Many were killed or wounded as were many of their White supporters. But they refused to be intimidated into passivity and silence and kept on marching.

Thus, today we have the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission, born out of this movement, whose responsibility it is to enforce minority ownership in the business, fair treatment on the job, equal pay for services rendered, and to uphold the controversial quota system throughout the federal government.

Immortalized as a great American leader, Martin entered the political arena as a revolutionary reformist, attempting to radically change the socio-political relations between Blacks and Whites in the South. Dominating the Civil Rights Movement, he changed American politics by creating genuine political power within the Black community through the ballot. Among his major achievements involving political empowerment were the “Civil Rights” and ” Voting Rights Acts. ” The Jesse Jackson phenomenon in 1984 and 1988, the David Dinkins and Douglas Wilder successes, along with the enormous impact that Blacks have made in American politics, would be virtually impossible without the achievements of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin’s moral ethics transcended the national boundaries of race. It was Martin who philosophically defined the political rationale of racial equality. He eloquently inspired Blacks to risk their lives for freedom and shamed many Whites into supporting his ideal of the American dream, an eventual reality where Blacks, Whites, Indians, Asians, Latinos, and others could live together as brothers and sisters, equal under the law, with an economic bill of rights that would guarantee income and job opportunities for all.

Martin became the moral conscience of America during his time. Regarding race relations in the United States and the world, no one understood justice with more depth or communicated it as powerfully as Martin. Because of him, not only is the world more aware of racial injustice, but also equally aware of its relation to poverty and war…As he stated in his famed “Beyond Vietnam” speech, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

In contrast, Malcolm, a revered revolutionary, was the force that almost solely transformed the way Black people thought about themselves. Politically, Malcolm was a Black Nationalist. He was quite critical of the Black masses and frequently told them that if their wretched condition was ever to change, they could not depend on Whites, the very ones who created the situation, to change it. He believed in Blacks evolving and developing a separate political agenda and plan of economic survival away from mainstream America to strengthen and mature as a nation.

He was the progenitor of the Black Consciousness movement that emerged during the 1960s which affected the entirety of Black life including Black aesthetics, Black studies, Black power, Black theology and Black pride. Malcolm’s dramatic impact was among the masses of African-Americans living in the ghettos of the cities. Malcolm advocated that Blacks should be proud of being Black. He further analyzed the dreadful psychological consequences of Black self-hate upon the consciousness of African Americans.

He once told a Detroit audience, “You know yourselves that we have been people who hated our African characteristics. We hated our heads…our noses…we hated the color of our skin…the blood of Africa that was in our veins. And in hating our features…why we had to end in hating ourselves. Our color became to us like a chain…It made us feel inferior”.

In listening to Malcolm eloquently transform their warped self-esteem, Blacks began to think and act “Black.” Through the power of his oratory, Malcolm made Blacks realize and accept Blackness as the essence of their humanity. “All of us are Black first,” he told African-Americans, “and everything else second.”

Malcolm in a charismatic way “decolorized the Black mind,” as Maya Angelou put it, and “thereby transformed Negroes into proud, Black, African people.” Mohammed Ali could then proclaim “I am the greatest,” Aretha Franklin starting demanding “Respect,” James Brown had everyone singing “I’m Black, and I’m Proud,” and as a people, African-Americans began to say to themselves and the world: “Black Is Beautiful.”

Stretching back to the African motherland, a cultural renaissance began to form and take shape. Dashikis and afros became outward signs of an inward metamorphosis. New, sacred places of worship were erected with African gods and goddesses as the objects of reverence.

Africa emerged as the continent of preference in defining one’s identity. Blacks today who are proud to claim their African heritage have Malcolm X to thank. He created the space for them to affirm their Blackness. So pervasive was his influence that even mainstream civil rights leaders, minister, and politicians acknowledged his insight and his integrity.

As a theologian, Martin was a master critic of American Christianity. Before him, White churches ignored the problems of racism, and Black churches passively accepted its consequences. He pricked the conscience of both Black and White Christians and began to enlist them into a mass movement against racism within the churches. He challenged the White Christians to be true to what they read in their Bibles and affirm that God created all people as one human family. He also challenged Black Christians to be obedient to the God they preached and sang about by refusing to obey laws that discriminated against them. He made racism the chief moral dilemma that all Christians had to resolve.

In American religion, as in American society, racism is deeply embedded. Malcolm was extremely critical of Christianity and the pivotal role it played in the mental and spiritual oppression of Black people. From the White biblical images to the missionaries sent to the “Dark Continent,” Malcolm felt Christianity was nothing but a form of White supremacy designed to make Blacks desire to be White. He felt that it was poisonous because it made one docile and made one turn the other cheek….it made one helpless. Malcolm discovered self-respect in Elijah Mohammed’s Nation of Islam because it was specifically designed to address the spiritual, social, economic and political needs of the Black underclass. When he heard the pro-Black, pro-Islamic, anti-Christian teachings, “It just clicked” he said. It was as if he was blind until Elijah Mohammed opened his eyes so he could see the world as it was. It was then that he realized that he hated himself, and wanted to be White, as did most Blacks. He also discovered why Whites hated Blacks. He was taught the true knowledge of himself and the history of Black and White people. Malcolm’s religious commitment was defined by his faith and the theology of Islam which stressed, self-esteem, strict justice, and stern punishment for America, because of her treatment of the darker races of people on earth. In his apocalyptic preaching, he warned America of its coming destruction because of her injustices.

One of the chief roles of a leader is to teach people how to organize themselves for the purpose of achieving their freedom. Both Martin and Malcolm realized that no people could achieve freedom as long as their leaders lack knowledge and understanding of how the economic and political systems of the world operate. Martin and Malcolm left us a legacy of linking the African-American freedom struggle in the United States with the liberation movements throughout the Third World. Like DuBois and Garvey before them, both men realized that the African-American struggle was not just a domestic affair, but also an international issue.

During his travels, Martin attended Ghana’s independence celebration in 1957 and Nigeria’s in 1960. He also made a month-long visit to India in 1959 to deepen his understanding of nonviolence as taught by Gandhi. His discussions with many persons in the Third World reinforced his belief that Africans around the world must unite in the struggle for freedom. At a Chicago press conference, he expressed these feelings, stating, “It’s part of something that’s happening all over the world…The oppressed peoples of the world are rising. They are revolting against colonialism, imperialism and other systems of oppression.”

Malcolm expressed an even closer connection between Blacks in the U.S. and Third World peoples. After his split with the Nation of Islam, he spent half of the last year of his life in the Middle East, Africa and Europe searching for religious and political directions in an attempt to develop a program of Black liberation. However, after these international experiences, he acquired a new vision of freedom that included the human rights of all. Malcolm once told a Columbia University audience, “It is incorrect to classify the revolt of the Negro as simply a racial conflict of Black against White…as a purely American problem…We are today seeing a global rebellion of oppressed against the oppression…exploited against exploiter. As important as Black Nationalism is for the African-American struggle, it cannot be the ultimate goal.” As a Black Nationalist, he emphasized that all non-European peoples of the world were part of one family, who together constituted the majority of humankind. Malcolm frequently referred to the 1955 Bandung Conference of Third World nations as a model of unity that Blacks in the U.S. should emulate. In his “Grass Roots” speech he called for a “Bandung Conference of Black Leaders” as early as April 1959, at a Harlem rally.

Malcolm experienced the importance of a Third World alliance during his first trip abroad when he visited Egypt, Arabia, Lebanon, and Africa. He then went to Nigeria and Ghana where he met Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah and addressed members of the Ghanian Parliament, as well as university students. During his second trip, he visited Egypt, Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon, Khartoum, Ethiopia, Kenya, Zanzibar, Tanzania, Nigeria, Ghana, Liberia, Guinea, Senegal, Algeria, Switzerland, France, and Britain. He also attended the second Organization of African Unity meeting in Cairo and held private conferences with African heads of states and leaders of liberation movements throughout the world. When Malcolm returned to the United States, he emphasized the linkage of our struggles and Third World liberation movements. “The only way we’ll get freedom for ourselves is to identify…with every oppressed people in the world…We are blood brothers,” he remarked.

Besides Martin and Malcolm’s accent on politics and culture, “internationalism” was their most important contribution to the struggle for freedom in this country. As powerful as DuBois’ Pan-Africanism and Marcus Garvey’s “Back to Africa Movement,” both Martin and Malcolm believed in Blacks uniting as Africans around the world. Because of both men, African Americans today are more internationally minded, universally supporting the anti-apartheid struggle of the poor against the rich. Freedom fighters everywhere have joined hands in Africa, Asia, South and Central America, Russia, and China to declare war on injustice.

What Martin and Malcolm have taught us is the importance of courage, intelligence, and dedicated leadership. Their solidarity with the masses of Black people and their unrestrained demand for Black people’s dignity, self-respect and freedom came with a price. Martin and Malcolm were both aware that the struggle might cost them their lives. Malcolm X made his feelings quite clear when he said before a New York audience, “The price of freedom is death… Respect me or put me to death.” And Martin also realized his life was on the line when he said “Freedom is not free…If a man hasn’t discovered something that he will die for, he isn’t fit to live.” In 1965, Malcolm was silenced by an assassin’s bullet in the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, New York. In 1968, Martin’s life was ended on the balcony of the Loraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, by a lone assassin. Both were 39 years old. Both were mentally and physically exhausted, and both were still fighting and searching for the freedom America promised and has yet to deliver.