THE POLITICAL AWAKENING OF IDA B. WELLS

by Paul Lee

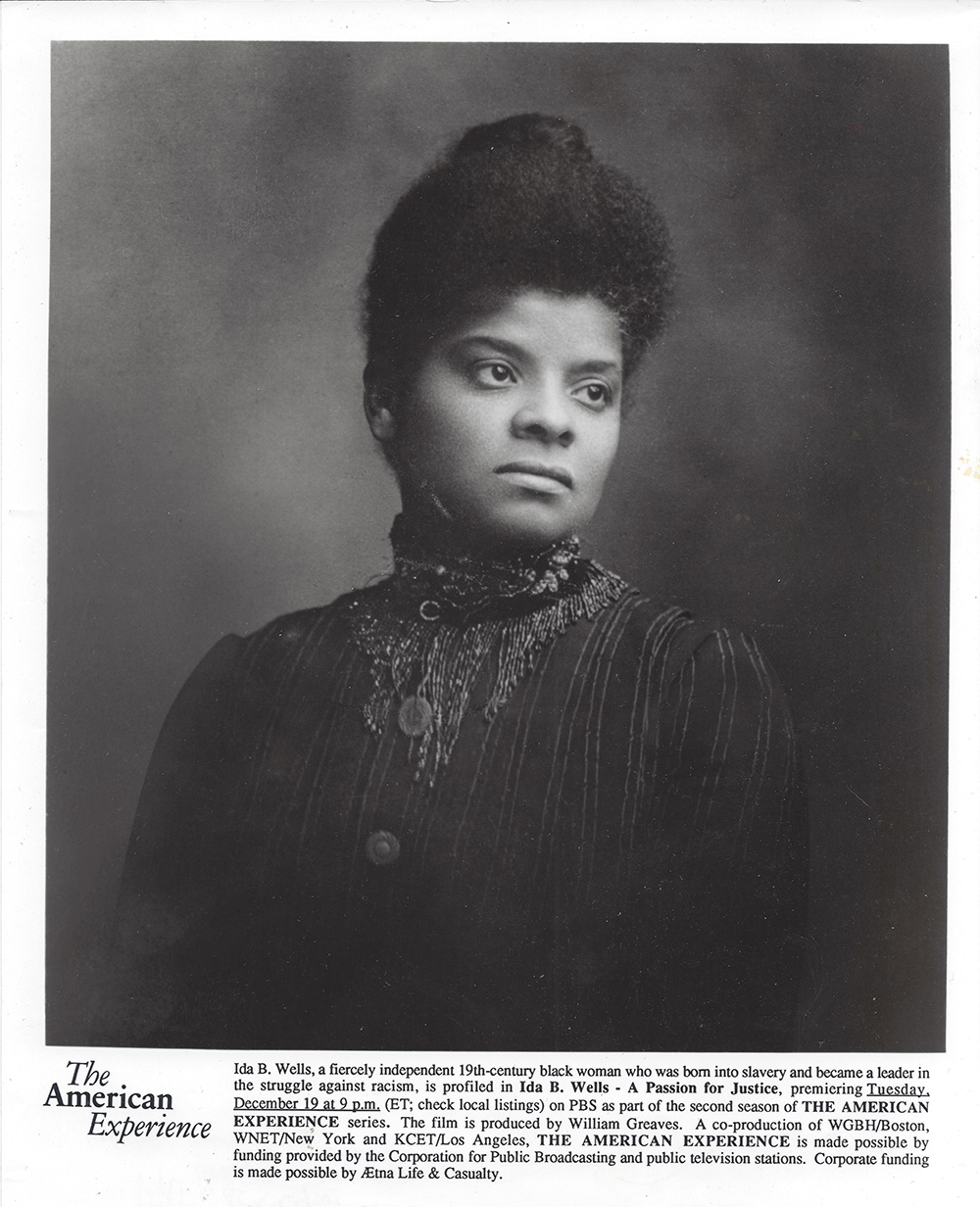

On the morning of February 13, 1893, a tiny, coffee-colored former school teacher appeared before the Boston Monday Lecture series at Tremont Temple. “It was…my first opportunity to address a white audience,” she later recalled in her autobiography. The series, organized by Joseph Cook, the famous preacher and social reformer, served as a platform for the presentation and discussion of the great social questions of the day. On this occasion, however, the young journalist-she was just a few months shy of her thirty first birthday-chose to speak of herself. Normally loathe to do so (her most intimated thoughts and feelings were usually confided to her diary), she had nevertheless begun to see the broader implications of the tragedies she had suffered and witnessed nearly a year before- the murder of friends which had gone unpunished; the disillusionment and terror which engulfed her community; the destruction of her newspaper when she dared to challenge the excuse given for such murders; and finally, her forced exile from her beloved home.

She had come to see these terrible events as symptoms of an escalating national epidemic that threatened much more than her person and the security of one community-it threatened the very freedom of a people only one generation removed from enslavement. Her talk, which she titled “Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” marked a critical stage in the campaign she would lead and which would thence-forth be inseparably linked with her name, Ida B. Wells.

In 1883, she sued the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad for damages after being forcibly ejected from a first-class coach that had been recently reserved for White ladies. (Their Black maids and nurses, however, were exempted from this rule.) The local courts decided in her favor, but in 1887 their verdict was reversed by the Tennessee Supreme Court.

Born a slave in Holly Springs. Mississippi on July 16, 1862, three years before the end of the Civil War, Ida Bell Wells was raised in the changed world of its wake in which, for the first time, equality was assumed as a fact. Her teachers at Shaw University (later Rust College), white Methodist missionaries, imbued their charges with the tenets of Christian egalitarianism by their teachings and their practice; and Northern carpetbaggers joined the freedmen in building the democratic institutions of the new Reconstruction government, But these exciting times came to an abrupt end for her in 1878 when both parents and a baby brother were consumed by a raging epidemic of yellow fever. Refusing to allow her family to split up, 16 year old Ida assumed responsibility for her five younger siblings by securing a job as a country school teacher. In search of greater security, she moved about 1880 to nearby Memphis, then fast emerging as a commercial hub and cultural center of the New South, taught in its segregated country and city schools, and gained entrance into the social life of its striving Black middle class.

In 1883, she sued the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad for damages after being forcibly ejected from a first-class coach that had been recently reserved for White ladies. (Their Black maids and nurses, however, were exempted from this rule.) The local courts decided in her favor, but in 1887 their verdict was reversed by the Tennessee Supreme Court. By this time, however, she had discovered what she later called her “first and it might be said, my only love”–journalism.

Writing under the pen name “Iola,” her earliest contributions-reports of local news, cultural reviews, and serious minded sermons on the virtues of piety, industry and economy-appeared in the local Black Baptist weeklies, and on occasion, the White dailies printed her letters to the editor. As her interests grew and her writing matured, her articles were picked up by many of the leading race “exchanges” throughout the nation, which numbered over two hundred in the 1880s. By 1889, she was acclaimed by her peers as the “Princess of the Press,” and in June of that year achieved a long sought after ambition by becoming part owner and editor of her own paper, The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight (later simply Free Speech)

But a virulent racist reaction was also on the rise during this period. In 1877, the promising reforms of the Reconstruction were betrayed by a political compromise between victor and vanquished which, by the 1880s and early 1890s, left African-Americans all but defenseless, especially but not exclusively, in the South. Legal and pseudo-legal barriers of discrimination were being erected and breaches in the developing new order were being increasingly fortified by the extra-legal sanctions of lynch law and mobocracy.

It was in this climate that an event occurred in 1892 that, as Ida B. Wells recounted in her autobiography story that she was invited to recite for the Boston Monday Lecture. The extracts that follow are reprinted from the text of her talk as printed in Our Day, edited by Joseph Cook, in May 1893. The editor has made several silent factual corrections.

“I am before the American people to-day through no inclination of my own, but because of a deep-seated conviction that the country at large does not know the extent to which lynch law prevails in parts of the conditions which force into exile those who speak the truth.

The race problem or Negro question, as it has been called, has been omni-present and all-pervading since long before the Afro-American was raised from the degradation of the slave to the dignity of the citizen. It is the Banquo’s ghost of politics, religion, and sociology. Times without number the race has been indicted for ignorance, immorality and general worthlessness–declared guilty and executed by its self-constituted judges. The operations of law do not dispose of Negroes fast enough, and lynching bees have become the favorite pastime of the South. As excuse for the same, a new cry, as false as it is foul, is raised in an effort to blast race character, a cry that has proclaimed to the world that virtue and innocence are violated by Afro-Americans who must be killed like wild beasts to protect womanhood and childhood.

Born and reared in the South, I had never expected to live elsewhere. Until this past year I was one among those who believed the condition of the masses gave large excuse for the humiliations and proscriptions under which we labored; that when wealth, education and character became more general among us–the cause being removed–the effect would cease, and justice be accorded to all alike. I shared the general belief that good newspapers entering regularly the homes of our people in every state could do more to bring about this result than any agency. And so, three years ago last June, I became editor and part owner of the Memphis Free Speech. As editor, I had occasion to criticize the city School Board’s employment of inefficient teachers and poor school-buildings for Afro-American children and at the close of that school-term one year ago, was not re-elected to a position I had held in the city schools for seven years. Accepting the decision of the Board of Education, I set out to make a race newspaper pay.

I became advertising agent, solicitor, as well as editor, and was continually on the go. Wherever I went among the people, I gave them my honest conviction that maintenance of character, money getting and education would finally solve our problem and that it depended on us to say how soon this would be brought about. This sentiment bore good fruit in Memphis. We had nice homes, representatives in almost every branch of business and profession, and refined society. There had been lynching and brutal outrages of all sorts in our own state and those adjoining us, but we had confidence and pride in our city and the majesty of its laws. So far in advance of other Southern cities was ours, we were content to endure the evils we had, to labor and to wait.

But there was a rude awakening. On the morning of March 9, the bodies of three of our best young men were found in an old field horribly shot to pieces. These young men had owned and operated the People’s Grocery, situated at what was known as the Curve–a suburb made up almost entirely of colored people–Thomas Moss, one of the oldest letter-carriers in the city, was president of the company, Calvin McDowell was manager and Will Stewart was a clerk. The young men were well known and popular and their business flourished, and that of Barrett, a White grocer who kept store there before the ‘People’s Grocery’ was established, went down. One day an officer came to the ‘People’s Grocery’ and inquired for a colored man who lived in the neighborhood. Barrett was with him and McDowell said he knew nothing, Barratt, not the officer, then accused McDowell of harboring the man, amd McDowell gave the lie. Barrett drew his pistol and struck McDowell with it; thereupon McDowell took Barrett’s pistol from him and gave him a good thrashing. Barrett then threatened (to use his own words) that he was going to clean out the whole store. Knowing how anxious he was to destroy their business, these young men accordingly armed several of their friends, not to assail, but to resist the threatened Saturday night attack.

When they saw Barrett enter the front door and a half dozen men at the rear door at 11 o’clock that night, they supposed the attack was on and immediately fired into the crowd, wounding three men. These men, dressed in citizen’s clothes, turned out to be deputies. When these men found they had fired upon officers of the law, they threw away their firearms and submitted to Barrette, confident they should establish their innocence of intent to fire upon officers of the law.

No communication was to be had with friends any of the three days these men were in jail; bail was refused and Thomas Moss was not allowed to eat the food his wife prepared for him. The judge is reported to have said, “Any one can see them after three days.” They were seen after three days, but they were no longer able to respond to the greeting of friends. On Tuesday the papers that had made much of the sufferings of the wounded deputies, and promised it would go hard with those who did the shooting, if they died, announced that the officers were all out of danger, and would recover. The friends of the prisoners breathed more easily. They felt that as the officers would not die, there was no danger that in the heat of passion the prisoners would meet violent death at the hands of the mob.

Besides, we had such confidence in the Law. But the law did not provide capital punishment for shooting which did not kill. So the mob did what the law could not be made to do, as a lesson to the Afro-American that he must not shoot a white man–no matter what the provocation. The same night the announcement was made that the officers would get well, the mob went to the jail between two and three o’clock in the morning dragged out these young men, hatless and shoeless, put them on the yard engine of the railroad that was in waiting just behind the jail, carried them a mile north of city limits and horribly shot them to death while the locomotive at a given signal let off steam and blew the whistle to deaden the sound of the firing.

“It was done by unknown men, “said the jury, yet the Appeal-Avalanche, which goes to press at 3 a.m., had a two–column account of the lynching. The papers also told how McDowell got hold of the guns of the mob, and as his grip could not be loosened, his hand was shattered with a pistol ball and all the lower part of his face was torn away.

“It was done by unknown parties,” said the jury, yet the papers told how Tom Moss begged for his life, for the sake of his wife, his little daughter and his unborn infant. They also told us that his last words were “If you will kill us, turn our faces to the West.”

I have no power to describe the feeling of horror that possessed every member of the race in Memphis when the truth dawned upon us that the protection of the law that we had so long enjoyed was no longer ours. The power of the state, county and city, the civil authorities and the strong arm of the military power were all on the side of the mob and of lawlessness. Few of our men possessed firearms, our only [military] company’s guns were confiscated, and the only White man who would sell a colored man a gun, was himself jailed, and his store closed. It was our first object lesson in the doctrine of white supremacy; and illustration of the South’s cardinal principle that no matter what the attainments, character or standing of an Afro-American, the laws of the South will not protect him against a White man.

There was only one thing we could do, and a great determination seized upon the people to follow the advice of the martyred Moss, and “Turn our faces to the West.” The Free Speech supported by our ministers and leading business men advised the people to leave a community whose laws did not protect them. Hundreds left on foot to walk four hundred miles between Memphis and Oklahoma. In two months, six thousand persons had left the city and every branch of business began to feel this silent resentment. There were a number of business failures and blocks of houses were for rent. The superintendent and treasurer of the street railway company called at the office of the Free Speech, to have us urge the colored people to ride again on the street cars.

There was only one thing we could do, and a great determination seized upon the people to follow the advice of the martyred Moss, and “turn our faces to the West.” The Free Speech supported by our ministers and leading business men advised the people to leave a community whose laws did not protect them. Hundreds left on foot to walk four hundred miles between Memphis and Oklahoma. In two months, six thousand persons had left the city and every branch of business began to feel this silent resentment. There were a number of business failures and blocks of houses were for rent. The superintendent and treasurer of the street railway company called at the office of the Free Speech, to have us urge the colored people to ride again on the street cars.

To restore the equilibrium and put a stop to the great financial loss, the next move was to get rid of the Free Speech–the disturbing element which kept the waters troubled; which would not let the people forget. In casting about for an excuse, the mob found it in the following editorial that appeared in the Memphis Free Speech–May 21, 1892:

Eight Negroes lynched since last issue of Free Speech–one at Little Rock, Ark., last Saturday morning where the citizens broke (?) into the penitentiary and got their man: three near Anniston, Ala., one in New Orleans–on the same old racket, the new alarm about raping white women;and three at Clarksville, Ga., for killing a white man. the same program of hanging, the shooting bullets into the lifeless bodies was carried out to the letter. Nobody in this section of the country believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men rape white women. If Southern white men are not careful they will over-reach themselves and public sentiment will have a reaction and a conclusion will be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.

Commenting on this, The Daily Commercial of Wednesday following said:

The fact that a black scoundrel is allowed to live and utter such loathsome and repulsive calumnies is a volume of evidence as to the wonderful patience of southern whites. But we have had enough of it. there are some things that the southern whites. But we have had enough of it. there are something s that the southern white man will not tolerate, and the obscene intimations of the fore going have brought the writer to the very outermost limit of public patience. We hope we have said enough.

The Evening Scimitar of the same day copied this leading editorial and added this comment:

Patience under such circumstances is not a virtue. If the Negroes themselves do not apply the remedy without delay it will be the duty of those whom he has attacked to tie the wretch who utters these calumnies to a stake at the intersection of Main and Madison Streets, Brand him in the fore head with a hot iron and perform upon him a surgical operation with a pair of tailor’s shears.

I had written that editorial with other matter for the week’s paper before leaving home the Friday previously for the General Conference of the A.M.E. Church in Philadelphia. Thursday, May 26, at 3 p.m., I landed in New York City and there learned from the papers that my business manager had been driven away and the paper suspended. Telegraphing for news, I received telegrams and letters in return informing me that the trains were being watched, that I was to be dumped into the river and beaten, if not killed; it had been learned that I wrote the editorial and I was to be hanged in front of the court-house and my face bled if I returned, and I was implored by friends to remain away. The creditors attacked the office in the meantime and the outfit was sold without more ado, thus destroying effectually that which it had taken years to build.

I have been censured for writing that editorial, but when I think of the five men who were lynched that week for assault on white women and that not a week passes but some poor soul is violently ushered into eternity on this trumped-up charge, knowing the many things I do, seeing that the whole race in the South was injured in the estimation of the world because of these false reports, I could no longer hold my peace, and I feel, yes, I am sure, that if it had to be done over again (provided no one else was the Loser save myself) I would do and say the very same again.

Following her exile from Memphis, Wells settled in New York City and was offered a regular column in The New York Age, the leading race paper, which was published and edited by her old friend, the brilliant T. Thomas Fortune, who was generally considered to be the “dean” of Black journalists.

Wells toured the British Isles, effectively internationalizing the question. She left behind her the London Anti-Lynching Committee to carry on the practical work.

On June 25, 1892, the Age devoted its entire front page to a meticulously documented expose of lynching by Wells, who signed the article simply “EXILED.” She frontally challenged the widespread justification for lynching, which was accepted by many blacks as well as Whites–namely, that the South was “defending the honor of its women” against the “brutal lust” of Black Fiends. Using statistics compiled by the conservative Chicago Daily Tribune, she pointed out the fact that “only one third of the 728 victims to mobs” who were lynched during the preceding nine years “have been charged with rape, to say nothing of those…who were innocent of the charge.” Moreover, lynch “law,” by its very nature, denied the accused of the presumption of innocence and the right to a fair trial, thereby subverting the rule of law by surrendering its prerogatives to the will of the mob.

At first, her appeals were directed at the “Afro-American” appears (she preferred the term to “Negro”) because, as she pointed out in Southern Horrors, a revision of her Age article published as a pamphlet in late 1892, they were “the only ones that will print the truth” about lynching. But she soon became convinced that the aid of influential Northern whites would be needed as well. In her autobiography, she recalled, perhaps with a mixture of satisfaction and frustration, that following her Monday Lecture appearance, “The Boston Transcript and Advertiser gave the first notices and report of my story of any White northern papers.” This, too, was considered insufficient, and in 1893 and 1894, Wells toured the British Isles, effectively internationalizing the question. She left behind her the London Anti-lynching committee to carry on the practical work. In 1895, she married Ferdinand L. Barnett, a lawyer, and settled in Chicago.

At the close of the century and the beginning of the next, Wells channeled her considerable energy into a variety of movements and causes–the Black women’s club movement, Women’s Suffrage, the fight against segregated schools, settlement house work to aid Southern migrants, the election of African Americans to public office–an inexhaustive list. She participated in the founding of two national civil rights organizations–the revived National Afro-American council in 1898 and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909–and actively supported two more militant groups–William Monroe Trotter’s National Equal Rights League and Marcus Garver’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. And, during all this, she was able to maintain what her friend Susan B. Anthony, the suffragist leader, called the “divided duty” of marriage and motherhood.

Because of her militancy, outspokenness, and refusal to compromise on what she understood to be matters of principle, she was more often than not a ‘lonely warrior,’ as historian Thomas C. Holt has called her. Though she anticipated many, if not most political and social strategies that were employed in the first quarter of the 20 th century, and even later, she was given little or no credit by her contemporaries and spiritual successors. About 1928, she sought to redress this omission, and the “lack of authentic race history of Reconstruction times” written by African Americans, by writing her autobiography. It remained uncompleted when she died at the age of sixty-nine on March 25, 1931, but was finally published in 1970. Edited by her daughter, Alefreda Duster, it was fittingly titled Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells.

Suggested Readings

Duster, Alfreda M., ed. Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells.

Giddings, Paula. “Woman Warrior: Ida B. Wells, Crusader-Journalist.” Essence Feb. 1988: 75+.

Holt, Thomas C. “The Lonely Warrior: Ida B. Wells-Barnett and the Struggle for Black Leadership.” In John Hope Franklin and August Meier, eds., Black Leaders of the Twentieth Century (Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1982), 39-61.

Sterling, Dorothy. Black Foremothers: Three Lives. Old Westbury, Ny: The Feminist Press, 1979.

Tucker, David M. “Miss Ida B. Wells and Memphis Lynching.” Phylon 32 (1971): 112-22.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. On Lynching. New York: Arno Press and The New York Times, 1969. (Reprints three of her pamphlets: Southern Horrors [1892], A Red Record [1895], and Mob Rule In New Orleans [1900].)

Wells, Ida B. “lynch Law In All Its Phases.” Our Day: A Record and Review of Current Reform 11 (May 1893): 333-47.

Paul Lee is a professional researcher based in Highland Par, Michigan. He served as chief researchist for the film ” Ida B. Wells–A Passion for Justice,” produced by William Greaves and broadcast on the PBS series The American Experience, December 19, 1989. He is presently working on a collection, “Iola”: The Writings and Speeches of Ida B. Wells, 1884-1894.