by Abdul Alkalimat

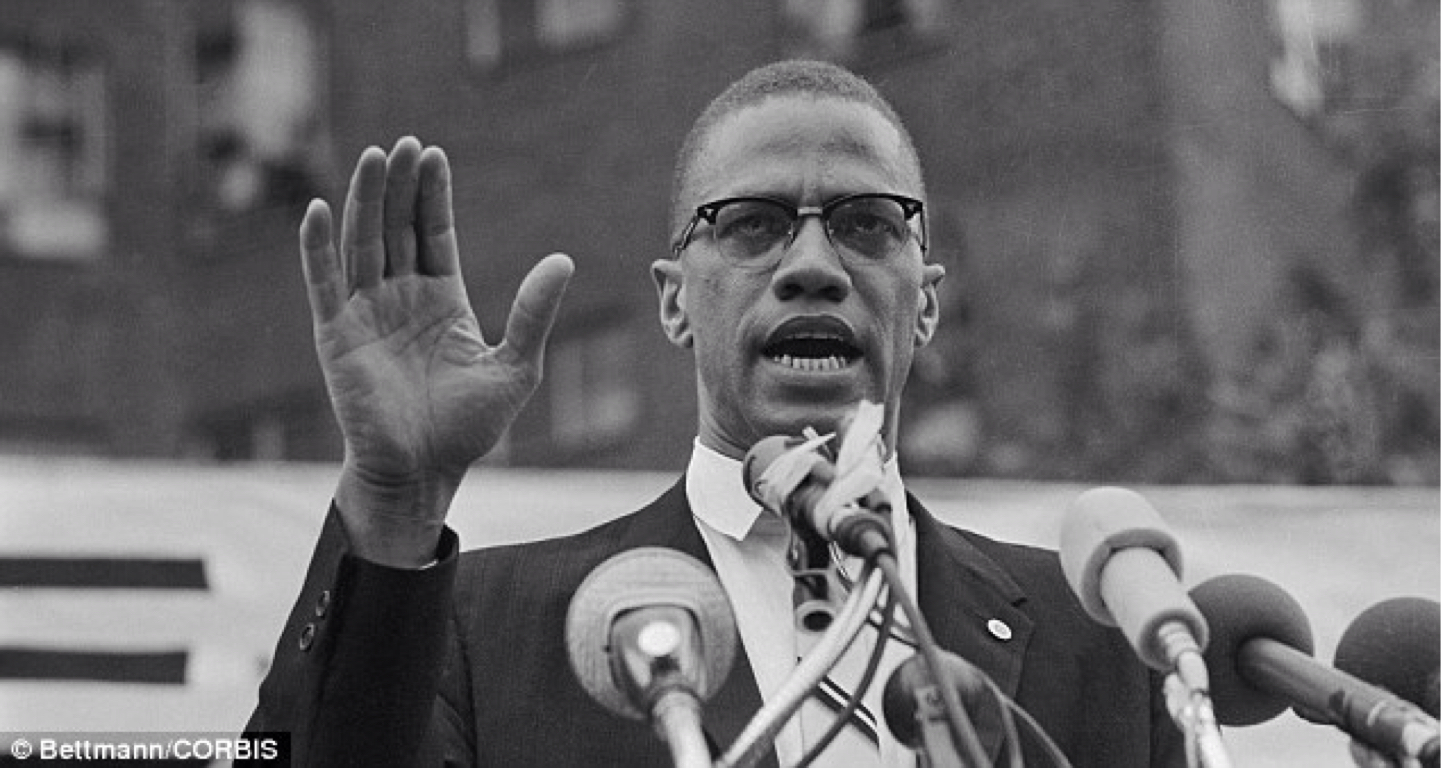

Malcolm X is the central figure in the most phenomenal revival in the history of Black political culture. While in the heart of every inner city ghetto Malcolm X was never forgotten, the last several years have seen a tidal wave of interest storm into the consciousness of Black youth throughout the world, including many third world youth and radical Whites as well.

Many people regard this as a fad and therefore reduce the Malcolm X revival to a basic American pattern, the transformation of an icon into a profitable commodity. After all, people in this country are taught that it is positive to sell anything you can to everybody. But from the point of view of the Black community this focus on Malcolm X represents a rebirth of consciousness and desire for change. It is this aspect of the Malcolm X revival that requires discussion if Black history is to be taken seriously, both its past and its future.

Even more than most people, Malcolm X was a man in motion. He experienced life so fully and so intensely in his brief forty years that one has to say he led several lives. Whenever someone attempts to define Malcolm X without regard to his full development he runs the risk of distortion. This is often done as a cover for sectarianism, for claiming Malcolm for one’s own political tendency. Evaluating Malcolm requires examining his entire life and not just one part of it.

With the collaboration of Alex Haley Malcolm wrote a classic autobiography in the great tradition of the slave narratives of Gustavus Vassa and Frederick Douglas and the autobiographical texts of Booker T Washington and WEB DuBois. This is our greatest single source of information about Malcolm X.

Malcolm was born May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, to Earl and Louise Little. His father was a Georgia-born Baptist preacher and an organizer for Marcus Garvey in the Universal Negro Improvement association. His mother was a Grenadian-born outspoken activist in the UNIA as well. He had nine brothers and sisters.

When Malcolm was six his father was brutally killed after suffering years of racist persecution, and six years later his mother succumbed to the pressure of the welfare system after trying to care for her children in poverty. She was committed to a mental hospital, where she stayed from 1937 to 1963.

After spending three years in a foster home and detention school, and still not escaping institutional racism and individual prejudices, he moved to Boston with his eldest paternal half-sister Ella Collins. In Boston he turned away from what he considered the critical imitative lifestyle of the Black middle class, and took to the cultural dynamics of the street, the nocturnal fast lane of pop culture.

First in Boston and then in New York, Malcolm explored the full range of illegal alternatives. He did everything that still haunts the Black community today: drugs, prostitution, robbery, violence in many forms. He formed a gang of thieves in Boston and quickly landed himself a prison term in 1946. At twenty-one he was a school dropout, a drug addict, and a convict. He put it this way in his Autobiography:

-

Looking back, I think I really was at least slightly out of my mind. I viewed narcotics as most people regard food. I wore my guns as today I wear my neckties. Deep down, I actually believed…one should die violently.

It was while incarcerated that Malcolm came to understand how he had been isolated and rendered powerless. At this extreme he experienced one of the great reversals of the 20th century, the rehabilitation and conversion of a hardened criminal. He met “Bimbi,” a prison intellectual, who taught him to respect language, books, and reasoning. Malcolm was also introduced to Elijah Mohammed, the leader of the Nation of Islam. These two men guided him to self-emancipation, to reading and writing his way to intellectual growth, and to a reversal of habits to reinforcing a new moral code.

He had gone into prison a degenerate criminal and after seven years had become a model of commitment, dedication, and discipline when he was released in 1952. Malcolm was now a man. He was moving in the path of his father, as a Black nationalist organizer attempting to save Black people from destruction by a white racist society.

For the next 12 years Malcolm became the main leader for the growth of the Nation of Islam from 400 to 40,000 members, with temples organized in virtually every major city in the United States. Malcolm went first to Detroit, then to Chicago to study with Elijah Mohammed. He was assigned to organize key cities. He became minister of the New York temple and national spokesperson for his organization and leader. He married and had six daughters.

Malcolm was an extremely devoted follower of Elijah Mohammed. However, strain developed, and on a personal and a political level the strain turned into conflict and led to separation. Mohammed was alleged to have fathered several children out of wedlock with two very young assistants, and in Malcolm’s eyes this was a devastating transgression exceeded only by the attempt to validate his behavior through biblical reference. Malcolm violated Mohammed’s mandate to remain silent after Kennedy’s assassination with his famous statement that “the chickens were coming home to roost.” Although he simply meant to say that “those who live by the sword die by the sword,” in Mohammed’s eyes this was an intolerable act of insubordination. Malcolm was silenced on December 3, 1963, and he formally proclaimed his independence from the Nation of Islam on March 8, 1964.

Over the next year Malcolm spent nearly six months abroad after announcing the formation of two organizations, the Muslim Mosque, Inc., and the Organization of Afro-American Unity. In this last year of his life Malcolm visited and lectured in over a dozen countries and established himself as a theoretical leader of the Black liberation movement. He had become even more dangerous outside of the sectarian Nation of Islam, since people from all parts of the Black community and from all over the world were searching him out and seriously considering his ideological and political leadership. He became an advocate of world brotherhood. But Malcolm was assassinated on February 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City, while lecturing to his followers. He was not yet forty years old.

The brief life of Malcolm X has become mythic in its implications. His career is a stark contrast to Martin Luther King’s. King was “to the Manor born,” a third generation preacher in a large middle class church in Atlanta, and a Morehouse College graduate with a Ph.D. from Boston University. Malcolm X was the son of an itinerant preacher who never had a permanent church, and he had to survive juvenile delinquency, a life of street crime, and drug addiction. Both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King became great leaders, traveling different roads and leading different parts of the Black community, but both were brutally murdered.

Martin Luther King had reached great heights of accomplishment, but Malcolm X had just begun to climb. Malcolm appealed especially to the “bottom of the pile Negroes,” as he used to call the homeless and the unemployed, because he felt himself to be a victim as well.

The question remains, was he a demon or a genius? There were many in the mainstream who would argue that he was a harbinger of hate and racial violence, but this was usually the reaction of Whites or middle class Blacks who were not used to hearing the honest and articulate voice of the suffering Black masses. Echoes of slavery and the lynch mob in the sayings of an urban working class Black leader shocked many. Malcolm forced America and the world to see itself from the eyes of the Black victim.

Malcolm was nurtured in the lessons of the radical Black tradition. This tradition has been produced anew by each generation on an ad hoc basis as each has had to face and fight racism and poverty. But this radical Black tradition has also been symbolically reproduced as the continuity of cultural legacy in opposition to oppression. Traditions like this are greater than the leaders who maintain them. This is what is meant by the statement that you can kill a freedom fighter but not the fight for freedom. Malcolm was murdered, but now he is being born again in the minds of a new generation of Black youth.