Nubian Art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts

Nubian Art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts

by Azell Murphy

Ancient Nubian civilization flourished for more than six thousand years. This sophisticated and unique culture is characterized by its own artistic development, central organization often led by a king, and during one period, a type of writing call Meroitic. Nubians created some of the earliest ceramics in the ancient world, as well as magnificent stone colossal sculptures. They built pyramids for their kings, and for over sixty years they ruled Egypt. Geographically, the area called Nubia overlapped southern Egypt and the northern Sudan. It is located from the first cataract of the Nile to the foothills of Ethiopia. This location made Nubia a transfer point between Africa and Ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, and the Christian and Islamic worlds. The Nubians were made up of diverse cultures which occupied this portion of the Nile River Valley. These cultures were linked by many common traditions but also distinguished by their unique works of art and individual customs.

The new gallery at the Museum of Fine Arts, provides an opportunity to highlight Nubia’s contributions to the world.

BOSTON – For centuries, cultures around the world have been fascinated by the ancient kingdoms of Africa. Royal pyramids, sophisticate tombs and burial customs, colossal stone statues, intricate hand-crafted pottery and exotic hand-crafted jewelry are a part of the African legacy that the Western world is just beginning to explore and understand.

A permanent gallery dedicated the art and culture of ancient Nubia, the region of Africa that is southern Egypt and northern Sudan, premiered at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston on May 10, 1992. The spectacular gallery, “Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa”, highlights more than 25,000 artifacts and original works of the ancient Nubian civilization, spanning six thousand years (6000 B.C. – 350 A.D.) of African history.

The ancient Nubian objects and materials on display were recovered during archaeological excavations conducted between 1913 and 1932 by the Harvard University Museum of Fine Arts and Boston. The Archaeological Expedition led by George A. Reisner, curator of the Department of Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern Art at the Museum of Fine Arts. The Egyptian government asked Reisner to head an archaeological survey of Nubia. The survey was necessary because of plans to enlarge the first Aswan dam built in 1899. When the dam was finished, the ancient remains of the Nubian cultures that existed between the first and second cataracts of the Nile would be lost underwater.

Reisner was so intrigued with what he found that he returned to Nubia to begin an in depth investigation. From 1913 to 1932 Reisner excavated massive mud-brick forts, temples and royal pyramids.

Reisner was so intrigued with what he found that he returned to Nubia to begin an in depth investigation. From 1913 to 1932 Reisner excavated massive mud-brick forts, temples and royal pyramids.

The government of Sudan agreed to award half of the objects found to the Harvard University- Museum of Fine Arts and the Boston Expedition, with the Sudan choosing first what it wanted to keep. Today, the Museum of Fine Arts, now houses the finest and most extensive collection of Nubian art outside of the Sudan.

In the gallery is a model recreating the tomb of Aspelta, an ancient king of Kush from about 600 – 580 B.C. in Nuri, Sudan. Attached to the actual pyramid was a small chapel in which the king’s soul was honored and fed in daily rituals. In the model, one side of the chapel is cut out, allowing the museum visitor to view its interior details. The original granite monuments and offering table that were inside the king’s actual tomb are exhibited in an adjacent case.

Below ground, the model’s burial chambers are cut out to allow museum visitors to look into the tomb and see a model of the king’s coffin. Although the original coffin was brought to Boston, it will not become a part of the museum display until the museum constructs a gallery floor strong enough to support the coffin’s twelve ton weight.

The kings and queens of ancient Nubian civilization had their tombs supplied with servant figures, known as “shawabtis” , which were believed to perform work for them in the underworld. One of the most spectacular displays in the gallery is an eighty-six stone “shawabtis” from the pyramid of King Taharka at Nuri. Taharka was the greatest of all Nubian pharaohs to rule Egypt and is mentioned twice in the Bible.

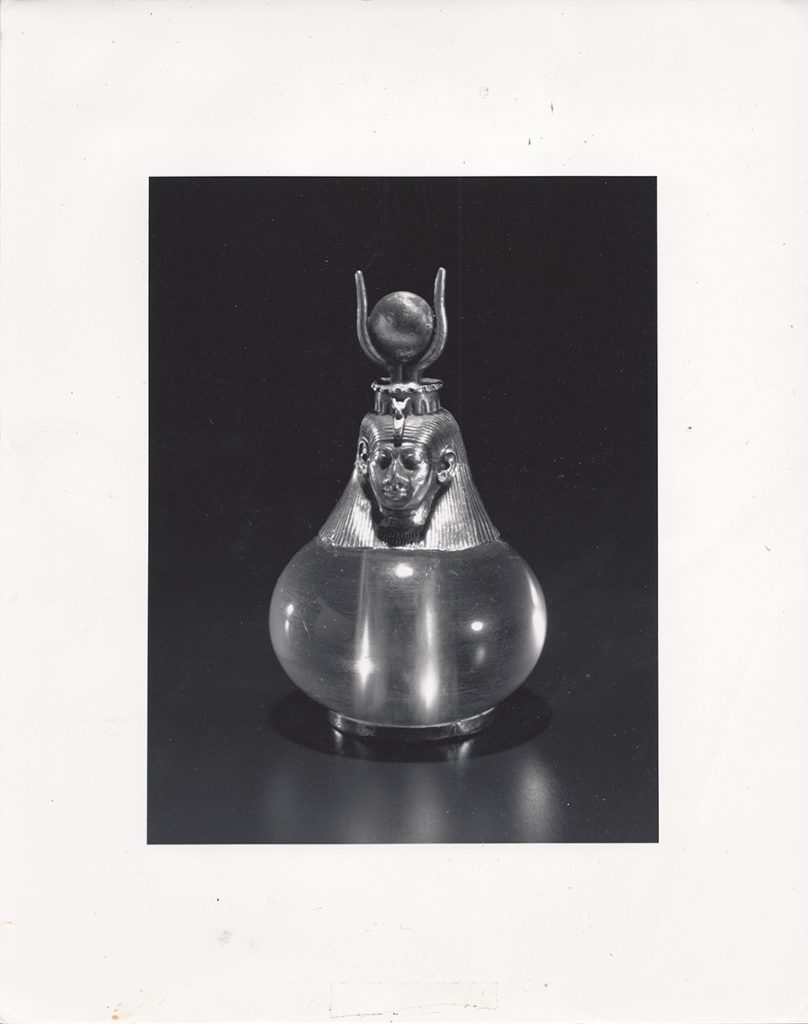

The Hathor crystal pendant is an extraordinary example of metal craftsmanship of ancient Nubian civilization on display in the gallery. A polished rock crystal globe is surmounted by a gold image of the head of The goddess Hathor. The head is finely detailed, manufactured from sheet gold that has been delicately modelled and refined. The crystal ball is pierced through the center, forming a shaft which is lined with gold and capped at the base. Jewelry designed with these kinds of internal chambers commonly held prayers or other charms to ward off evil. This remarkably beautiful piece dates back to the eighth century B.C. and was found in the tomb of an unnamed queen of King Piye (a great king who conquered Egypt about 720 B.C.), and was probably worn by her as a pendant. Nubians created some of the finest ceramics of the ancient world. Delicate and creative vessels made by the Kerma culture (2000 – 1550 B.C.) are on display in the Nubian gallery. The crafters of this pottery achieved an eggshell thinness and remarkable symmetry. Pottery shapes include the fine bell-mouthed cups, delicate long-spouted jars and a ram-head pitcher.

Besides showcasing great Nubian accomplishments, “Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa” educates museum visitors about Nubian historical figures. The great King Piye who conquered Egypt is represented by a magnificent bronze offering table found in his tomb. A fold handled mirror of his brother and successor Shabako is on display. A statuette of Piye’s son Taharka is one of the most expressive displays in the gallery. Taharka, built his pyramid in Nuri, Sudan, which was excavated by the Boston Museum in 1917.

According to museum officials, conservation and restoration of over a hundred fragile or fragmented objects that had never been displayed since their arrival in Boston more than seventy years ago was the most troubling of all planning stages for the finished gallery. Two stone monuments that were shipped to Boston as several blocks of carved sandstone were the largest and most extraordinary reconstruction tasks.

One consisted of twenty-three blocks that made up the interior walls of a Nubian king’s pyramid chapel of about 300 A.D. Found as a part of the ruins of a pyramid in Meroe, Sudan, in 1921, the walls show the king seated on a lion throne, protected by the winged goddess Isis. On one side he is greeted by male courtiers, while on the other side he is greeted by the chief queen and female courtiers.

Before this object could be reconstructed, the individual stones had to be specially treated because of their brittle and unstable condition, museum officials say. The treatment was a complex process, requiring their movement to a specially ventilated room, where they were treated with a liquid stone strengthener.

The installation of the “Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa” gallery at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston was made possible through grants from the NYNEX Foundation and New England Telephone. Additional support was provided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Federal Agency.